Final Summary of Project ActivitiesThe PEER team began by training CLP members, park rangers, and MNP staff on survey methods, identification of target taxonomic groups, basic principles of climate and climate change, and installation and monitoring of climate stations. The PI and her U.S. partner also installed two microweather stations at each site to help determine whether climate has had an impact on biodiversity. During the first data collections, student researchers followed and collected data alongside CLPs, in order to ensure that CLP practices and data recording were accurate. Once confirmed, CLPs independently collected data monthly for six months. Students from the University of Antananarivo also collected biodiversity data in the same sites as the local community for comparison purposes .

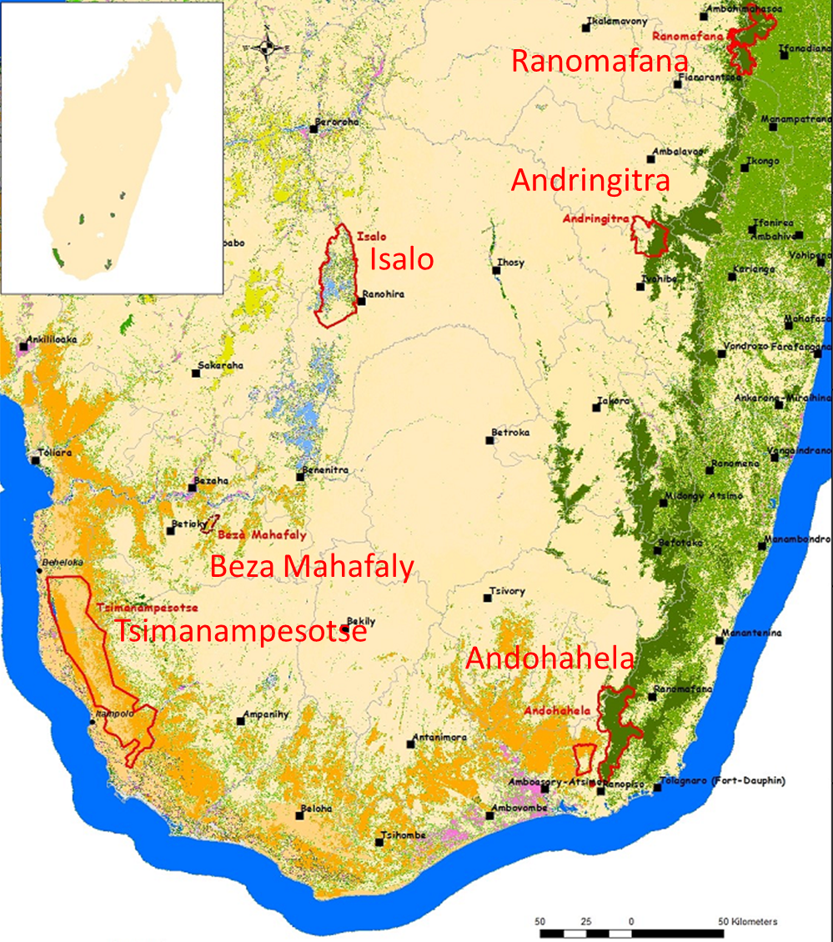

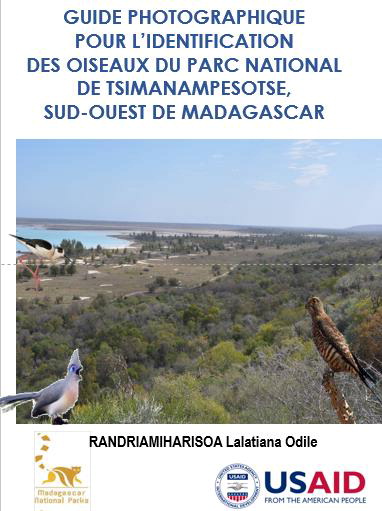

By comparing the species identified by local community members in the six protected areas, the researchers found that community members were able to perform about as well as experts. The results suggest that community members saw about as many species as experts (and on average, a bit more). However, experts saw higher per species abundance on average, in large part because they saw far more individuals of common species. The numbers of species encountered by the CLPs and experts were almost the same across the four protected areas. On predicted species accumulation, after 150 days of monitoring effort, community members reached a plateau of improvement. Overall, the project showed an improvement in the quality of data collected on biodiversity, both by the local communities and by the park officials. This improvement was partly due to access to the identification guides originally produced at the start of the project and partly thanks to enhanced data collection in the field made by the PEER team and their trainees during the project.

The biodiversity monitoring method for this project has been adopted by each park. The monthly rounds by local community members have led to a crackdown on unauthorized people roaming in the protected areas, which may have reduced the number of trees illegally cut. Participating local communities exchange visits in each protected area, which was notable as many people involved had never traveled before. The exchange visits strengthened collaboration between the CLPs and the MNP staff.

The concept of women working as part of the local park committee resulted in a heated discussion during one exchange, as Andohahela National Park has eight female participants. That surprised CLPs at other parks where women are not allowed to participate, and yet, based on women's effective participation in this project, it is evident they are all as capable to work in conservation as men. According to the PI Dr. Randriamiharisoa, the women have been even more effective than the men in raising awareness of the relevant issues. The CLPs received compensation for their participatory work, and for some their earnings became their monthly source of income. Some participating community members were able to increase their livestock or poultry and further their agricultural activities, others were able to buy household supplies, while others used the funds to send their children to school.

The PEER team created and hosted a new workshop on structuring and cleaning databases and data analysis that can serve as a new ecological training program. They presented their findings at the 2022 annual meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation in Cartagena, Colombia, and were awarded a new $79,000 grant from the Foundation for Protected Areas of Madagascar (FAPBM) for a similar project focused on vegetation monitoring.

PublicationFiona Price, Lalatiana Randriamiharisoa, and David H. Klinges. 2023. Enhancing demographic diversity of scientist-community collaborations improves wildlife monitoring in Madagascar.

Biological Conservation 288: 110377.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110377